I am Dr. Donna Oliver, a social scientist who perhaps loves nature a bit more than humanity. Experiencing the Coriolis Effect at Ecuador’s equator (0 degrees latitude) was a super-spiritual and mind-expanding reminder of the orderliness of some aspects of life. The equator is the widest point of the planet and the poles are the smallest. One rotation of the planet still lasts 24 hours in both places, which means the surface of the earth is spinning faster at the equator than at the poles. In equatorial regions the surface of the earth is spinning at nearly 1,000 miles an hour and at the poles the surface crawls along at 0.00005 miles per hour. I lamented why human behavior could not be so orderly and predictable!

Someone standing on the surface of the planet doesn’t notice the difference in speed, but it becomes more noticeable in the air. In the Northern Hemisphere the air circulates to the right and in the Southern Hemisphere the air circulates to the left. This effect is responsible for ocean currents and trade winds that have enabled humans to explore our planet.

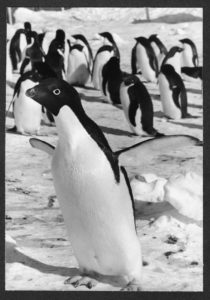

Precisely a quarter of the globe’s circumference away, ninety degrees south of the equator, nature is quite different. The geographic South Pole is topped with 9,000 feet of ice. It is far from possible for anyone to stand on real ground. Temperatures range from a low of -115 degrees F to a high of -15 degrees F. The air is “thin.”

It is challenging for humans to acclimate to the south pole extremes where the world nearly stands still. . . and human nature dictates that only eccentric people are attracted to the southern polar region.

In spite of my love of nature … my four college degrees (PhD, MA, MA, BA) are all in the human sciences. I did find a way to experience one of the harshest natural environments on earth while studying people intermingled there. In 1977 I was one of seventy-eight kooky subjects in my polar research group, all wintering over at an Antarctic base, with no escaping for seven months.

My data and all subjects survived. The resulting dissertation was “The Psychological Effects of Isolation and Confinement in an Antarctic Winter-Over Group.” Standardized test results were carefully administered and statistically analyzed, and my findings disseminated. Results were widely presented in various venues, from the heights of a PBS hour-long TV special and a chapter in a NASA book, to the lows of misquotes and a fake nose in a National Enquirer article.

As many Old Antarctic Explorers attest, polar life can become an obsession and dictate one’s life until death. In 1978 I decided to close out that chapter of my life. Not yet thirty and already an expert in my field of isolation psychology—simply because I was one of the first psychologists to experience those conditions firsthand—I wanted to stop looking back. I had an entire lifetime in front of me, and I wanted to be available for so many new opportunities. And so, even though my most interesting polar data was not yet analyzed, I placed it out of sight, in storage, where it remained for forty-two years.

I was the third woman, of any nation, to winter on the continent. The two who preceded me wintered together in 1974. They are deceased, making me the longest-surviving, and leaving me to describe the challenges of being the earliest south polar winter female explorers.

In 1977 I wintered with seventy-seven men, mostly rough-and-tumble Navy Seabees, at McMurdo Station. The winter crew consisted of seventy-two support personnel who kept the base running for six researchers. Three of the support personnel were hired by a private support company, and sixty-nine were in the Navy.

The sixty-nine military men voted, unanimously, to appeal for my departure before station closing. But recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions had made it illegal to ban workforce employees because of their sex, and I beat the men’s appeal. I stayed on, the only woman on the entire continent for seven months.

I kept a journal there, 640 handwritten pages, recording my Antarctic experiences. Actions by individuals and institutions to illegally ban female presence are documented; in some instances, Navy personnel-men snuck letters to me against their commander’s dictate to “not show to anyone!” Exciting adventures, breathtaking natural beauty, dangerous events, and the boring long night are recounted.

Unrivaled attention was given in my writing to the often humorous stories, eccentricities, and relationships of co-winterers. Some of my most staunch opponents eventually became friends. The Navy chiefs were adamantly against female presence, yet with time, our relationships warmed. I joined them for Saturday night poker and held my own. They were particularly sweet at our final game and complimented me, “Donna, you really did survive the winter well.” I was thrilled, but my heart dropped when they added, “But we don’t know any other woman who could.” I had worked so hard to prove that some women—just like some men—were physically and emotionally strong enough to winter. Instead they made me into the only superwoman who could.

As for my lament that, unlike the Coriolis Effect, human behavior cannot be orderly and predictable, perhaps it can be predictable. The theory of cognitive dissonance addresses what happens when humans hold very strong beliefs that something is true. When an event occurs contrary to their belief, instead of modifying the basic known “truth,” they make the new occurrence an exception in some way.

Women can’t survive winter here. Donna is a woman who survived, but Donna is a superwoman exception. Women can’t survive winter here!

I did not change their minds, but it was fun taking their poker money.

What compelled me to finally uncover my journal? On a personal level, after decades of a personally and professionally fulfilling, and wonderful, polar-free life, it was now harmless to look back. But it is on the societal level that sharing stories from the journal is imperative.

The struggle for gender equality—to be seen as complete and capable in one’s own right, not primarily as a possession for the comfort and furtherance of men—still permeates our culture. It is often a bit more camouflaged than in 1977, yet it remains rampant. Consider just one example: A man bragged, while being filmed, that he can grab a non-consenting female stranger “by the p****” because he is famous. And instead of going to jail for assault, he went on to run the White House. We still have a lot to accomplish in the arena of gender equality!

My historical writing provides many illustrations that can help us better understand where we’ve come from and where we are at this time. With a more complete picture of our history, we are better equipped to make new leaps forward now.

— Dr. Donna Oliver, December 2023

Contact Dr. Oliver

Feel free to email me at:

Dr.Donna@drdonnaoliver.com

Or reach out on social media at:

Instagram @drdonnaoliver

Facebook @drdonnaoliver